The best horror movies on Hulu right now

A scream in the night. A vindictive spirit. One last girl runs to safety. Sometimes you just want to watch those classic horror stories and hit those favorite horror beats. Luckily, if you’re in the market for some streaming screams, Hulu has a solid lineup of horror movies to work with.

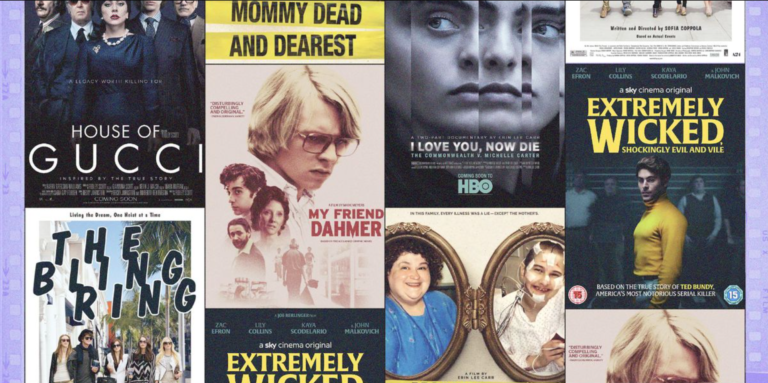

Fresh (2022)

In debut director Mimi Q’s fun and hilarious horror “Taza,” Nova learns all about the losers in her poor menu of endless app scrolls — understandably, she’s lost her taste for kissing frogs. Is. Still, our modern West Coaster — charismatically played by “Normal People” breakout Daisy Edgar Jones — refuses to give up hope and puts herself out there as a courageous, scarf-wearing douche. Woe be damned friends! It’s because of her sweet hope that she stumbles across countless falsely cool profile photos during one such evening of mindless browsing, and ends up with someone who sports a photo of a cute dog as her avatar. have been But what does she thank her curiosity for? Nothing, just a gross dick pic sent by your average creeper.

We’re introduced to Nova in a great opening scene during a terrible date with one of the aforementioned scarf wearers. A cheapskate (“Bring the cash,” he reminds Nova before the date), Chad chews his noodles and spews all sorts of stomach-churning vitriol. “You’d look great in a dress,” he says unkindly to the sweater-wearing Noa, putting her down as “like women of your parents’ generation” for not being feminine. He insults their waitress with blatant racism. He feels entitled enough to grab all the leftovers, doesn’t bar the door for Nova (what happened to all that “parents’ generation” talk?) and isn’t reciprocated when he reaches out for a kiss. If found, it is called a trapped dog. So can you really blame Noa for buying into Steve’s grand gestures of Sebastian Stan’s traditional charm and falling into bed with him on the heels of that disastrous evening?

You can’t—hey, this is the ever-charming Stan we’re talking about—but you’re allowed to raise a slight eyebrow when this practical woman completely trusts a perfect stranger She just met him in a supermarket aisle, allowing him to take her to an unknown destination for a surprise weekend. Thankfully, her droll, bisexual best friend Molly (a terrific JoJo T. Gibbs) who seems to have given up on men altogether, has sharper instincts. No social media footprint? Not even an Instagram page for someone who claims to be a plastic surgeon? To Molly, these are all red flags.

He’ll also seem pretty shady to viewers, thanks to Lauren Kahn’s zippy script and cavernous visual language that, in one-dimensionality, suggests a lot of uneasiness beneath Steve’s laid-back charm. “I don’t eat animals” from his lips will ring an alarm bell or two to alert ears. (Why not just say “I’m a vegetarian?”) Other clues will also hint at the colors of this mysterious man’s unusual taste buds. But it’s not until the title card appears more than 30 minutes into the “fresh” film that they’re spelled out for all their badness. (Speaking of late-rising title cards, if “Drive My Car” was a bridge too far for you in that department, wait until “Fresh” sneakily claims, “My Hold on old fashioned!”)

While the surprising twist from this point is what sickly fun “Fresh” is about, it’s nearly impossible to talk about this movie without spoiling it somewhat. So read everything below at your own risk, knowing that if you do, your first experience with the film will be irrevocably changed. Here it goes: Steve is actually a cold-blooded liar as well as a cannibal, satisfying his needs by selling processed female flesh to his ridiculously rich cannibalistic clients. Nova is just the latest of his victims to take the bait. But there seems to be something different about her approach to him, as she quickly learns through cell-to-cell prisoner banter in Bluebeard’s ruthless dungeon. It seems he actually likes Nova, and maybe he has a way to use his infectious smile and seductive femininity to outwit this serial killer.

I’m making this all more serious than it really is. Realize that the irresistibility of “Fresh” lies in the fact that it doesn’t take itself too seriously—all things considered, the film lives up to its “Hostel” concept of “Ex Machina.” Manages to stay light on her feet, avoiding most appearances. Her mildly feminist story preaches self-righteousness where women’s bodies are perishable objects. In this sequence, Cave and his cinematographer Pawel Pogorzelski (a frequent Ari Aster collaborator) present a buffet of men enjoying their expensive meals, keeping the mood nimble and goofy. PhBell’s “American Psycho” practices on this occasion. (Peter Cetera’s “Restless Heart” and AniMotion’s “Madness” come to mind as two viciously comic scenes.) Gibbs is also the film’s secret weapon—while his character is menacingly a stock “support” on the page. Close to a “black best friend”, Gibbs defies the clichés and claims Molly as his own.

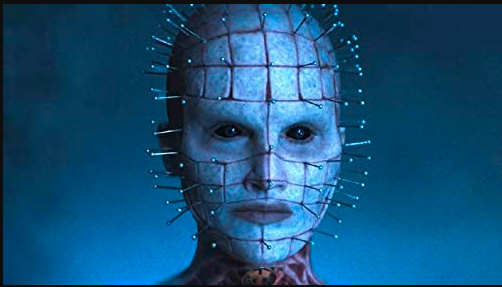

Hellraiser

Watching the original “Hellraiser” still feels like taking on a desecrated, if by now familiar, episode. In this film, Barker introduces readers to the Cenobites, a race of god-like sadists who terrorize their human victims into sexual experiences beyond their (or our) jaded understanding of pleasure and pain. . The new “Hellraiser” evokes Barker’s original adaptation the way a good cover song evokes its source material: with love, intelligence, and inevitably crushing futility. Nobody really needs “Hellraiser,” but it can still be fun sometimes, especially if you haven’t seen “Hellraiser” in a while.

This “Hellraiser,” 35 years after the original and nine sequels, feels dutiful and stagnant where Barker’s version reflected his unique sensibilities and preoccupations. The cleverest addition to the “Hellraiser” canon will only be apparent to die-hard fans as the makers of the latest film have awkwardly grafted a sometimes affecting monster movie onto the back of a trauma-focused character study. Riley (Odyssa Azion), a grieving ex-addict, runs into Cenobites chasing her missing brother Matt (Brandon Flynn), who first set Riley up with her sketchy boyfriend Trevor (Drew Starkey). He was scolded for staying.

Bruckner also acknowledges that his strong, but not quite retrospective, feature, “The Nighthouse,” suggested his unusual indifference to character and narrative continuity. Even the agonized departure of Voight’s jaded assistant Serena (Hayam Abbas) seems unnecessary as her personality is reflected neither in establishing scenes nor in her seemingly unbearable clashes with the cenobites. It’s always nice to see Abbas pop up in English-language productions, but the poor woman can only do so much with a supporting role that’s more than a person.

Still, if you’ve seen or cared about Barker’s “Hellraiser,” you’ll likely enjoy Bruckner’s “Hellraiser.” This updated version doesn’t hang very well from scene to scene, and it doesn’t really expand on Barker’s original character concepts, which were really just sketchy plot suggestions to begin with. But, however, there are enough cheesy callbacks and luscious moments that keep you waiting for something to happen.

A dedicated score by director David Bruckner (“The Nighthouse,” “The Ritual”) and co-writers Ben Collins and Luke Piotrowski, however, doesn’t meaningfully connect the cenobites with Riley or her character’s defining convictions. That he is the target of forces beyond his control. She’s fine, and so is Matt, who disappears shortly after he and Riley’s breakdown. They argue about Riley’s erratic behavior, which most likely means her relationship with jock Trevor, who drinks around Riley despite attending a 12-step program.

Neither Trevor nor Matt’s relationship with Riley develops much over time (it’s 121 minutes long, folks), as most of the plot revolves around the arrival and eventual disappearance of the Cenobites. They follow Riley as she steals and accidentally opens a puzzle box containing gold. But Riley just steals the box, which horror fans will instantly recognize as a way to summon cenobites, as Trevor encourages her. Riley further immerses herself in the story of the Cenobites—which links the box to its former owner, the ambitious rich man bohemian Mr. Voight (Goran Visnjic)—in the vain hope that mastering the box will lead Matt to his The pass will be returned.

The rest of the characters in this new “Hellerizer,” including Matt’s boyfriend Colin (Adam Faison) and Riley’s roommate Nora (Avaif Hinds), are the only figures who risk any situations arising from Riley’s quest for answers. can react. This general lack of personality wouldn’t be so bad if there weren’t so many deaths throughout One Hundred and Twenty-One that basically gives viewers time to wonder who these new cenobites are and why they now have vague personalities. . . Get all the attention of well-restored hand-me-downs.

It’s true that the Cenobites’ new designs make them look suitably unnerving, and they’re thoughtfully presented here as an interdimensional shark lazily circling Riley and her friends. Reflexes establish cruelty. Bruckner, who has already established his reputation for impact-driven shock horror in his two previous features, backs it up with some memorably disturbing moments. (I didn’t expect a REDACTED to enter REDACTED’s REDACTED.)

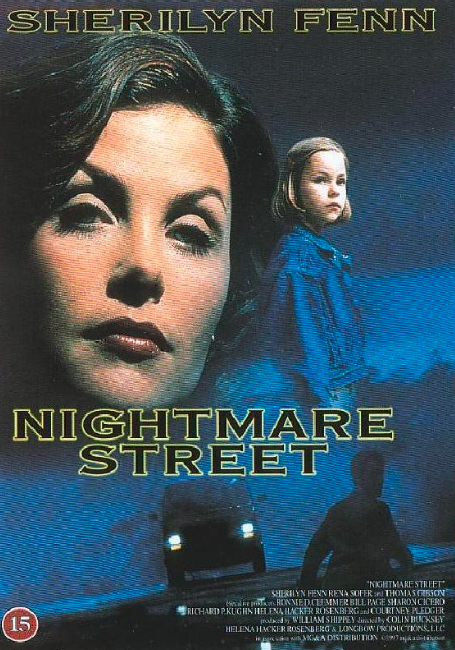

Nightmare Street

That we can guess exactly where Stan’s road leads isn’t just because of Edmund Golding’s 1947 film adaptation or William Lindsay Grisham’s original novel. Even those unfamiliar with one or both of the materials can detect del Toro’s cyclical allegory through the understanding and reworking of noir tropes, both visually and thematically. His “Nightmare Street” is a film about psychological tunnels and downward spirals. Upon entering them, Stan runs the risk of getting lost and never coming out the other side.

The circular symbol is most clearly seen in the rotation of an imposing Ferris wheel. Even more prominent in Tamara Durrell’s impeccable production design aesthetic, heavy on the green and gold hues, is the unsettling depth of the world when Stan arrives in Buffalo, New York: the long corridors, spacious offices, and narrow streets that film Meets dramatic needs. . More than period accuracy.

Deverell’s work is inimitable in conversation with cinematographer Dan Lostson, now on his fourth outing with the Mexican filmmaker, whose single-source lighting choices lend the actors a timeless, shimmering glow. There’s the flawless artistry, and then there’s del Toro’s productions, an almost unparalleled level of detail at least as it relates to genre cinema. Del Toro’s signature monsters are not entirely absent from his new vision, as a pickled creature named Enoch, with a third eye, floats in a state between art and myth.

At the carnival, Stan meets an elite ensemble of eccentric personalities. Among them, two of del Toro’s former colleagues, Joe Clifton Collins Jr. and Ron Perlman, played small parts. But it’s in odd couple Xena (Toni Collette) and Pete (David Strathern) that “Young Deer” discovers a new calling. With a sophisticated word code, they can pretend to read minds and guess objects while blindfolded. Harnessing his powers over the average person’s distrust becomes the scheming anti-hero’s goal, as he also courts Molly (Rooney Mara), another corny victim of his snobbery.

As one of Hollywood’s most interesting stars in terms of his choice of role, Cooper works magic with an exceptionally whimsical turn that takes his Stan’s pace from the dubious to the absurd. Huda maps to confidence and ultimately pathetic resignation. The aim here is not to imitate the wind of a classic star, but to make these changes believable enough to make us doubt its indifference.

There are only a few obvious changes between the 1947 iteration and del Toro’s 21st-century interpretation, namely a deepening of the characters’ motivations and existential variations. Stan’s father issues, for example, gain greater relevance through the embodiment of a boy in Cooper’s body who is still crying out for validation, and the world in the guise of success to demand it. is angry against

Take as proof an early scene at Xena and Pete’s house where the big man shows off his manipulative tricks. Stan, presenting himself as a bright-eyed dog of a man, arrives to demonstrate that he had a difficult relationship with his father. For a moment he felt emotionally exposed to the sense of recognition of another, only to discover that he was only part of the common denominator. He was reading Pat’s words like a proof book.

“People are eager to see,” Pete said. “People are eager to tell you who they are.” Pathetic yet piercing, the truth packed into this sentence is bone-chilling. He cautions against “spook shows,” playing with the fire of pretending that one has supernatural powers that can communicate with the afterlife. Naturally, Stan is exactly what he pursues when he escapes the countryside for the big city with Molly.

It is his greatest achievement that Stan comes into contact with the unscrupulous Root Dr. Rutter (Cate Blanchett), a psychiatrist who has a disdain for people like him who mislead the wrong people with their cash. Cheating. With delicious mischief, Blanchett creates a shrewd femme fatale equipped with intuitive people-reading skills and the information she stores. The actress, a paragon of beauty, stands out for her deliberately vicious gestures and pointed interrogation that rips her antagonist’s face off. Never underestimate Blanchett’s uncanny ability to push beyond her own gold standards.

The longer Lilith interacts with Stan, the more blood she goes for, repeatedly drawing out the beautiful charlatan of her fragile self-esteem with each session. Those tête-à-tête sequences with her and Cooper in his opulent office provide some of the film’s most interesting encounters, as the weak link emerges from the switch in the power dynamic. As Stan becomes intoxicated with the power he realizes when he convinces rich old men that he can communicate with the afterlife to atone for their sins, the closer he gets. He gets closer to his mother

Hypnotic with its fast-paced slow-burn plot development and captivating atmosphere, “Nightmare Street” pulls viewers down with its self-imposed edge. Unbridled greed eventually throws Stan into a hellish circle of his own making, or perhaps, if one wants to embrace empathy, that stems from his tendency to try harder to fill the void. . Whatever the case, the film’s final shot, though deliberately predictable, resonates as a tremendous tragedy.

Bad Hair

The best thing I can say about Justin Siemian’s dark hairstyle horror satire “Bad Hair” is that it made me want to put a killer on my head. I’ll look like Tulsa Doom from 1982’s “Conan the Barbarian” but I’m fine with that. I’ve always wanted to rock my hair like Cab Calloway. Besides, I have scores to settle. Creature feature horror is one of my favorite genres, and I evaluate them to see if I’d like to own a monster. In this respect, the film succeeds: while it ultimately doesn’t live up to its established canon, The Killers is visually stunning. It thrives on blood and is not picky about where it comes from or who it has to kill to get it. Like “The Blob”, it has the ability to reshape itself while hunting prey. It also lights up the eyes of its owner, Anna Bledsoe (Elle Lorraine), while giving her flashbacks that look like Kwanzaa greeting cards.

Where “Bad Hair” isn’t quite as successful, however, is in the hornet’s nest it kicks in regarding its subject matter. At nearly two hours, Siemian has time to interrogate the natural-versus-processed-ball argument rather than occasionally allude to it. It only took Spike Lee six minutes to create such dialogue in the “Straight and Nappy” number in “School Daze.” The movie came out in 1988, a year before “Bad Hair” happened. The lack of focus on this controversial issue is more a product of the screenplay than it can chew. We also have to deal with sexism in the workplace, racial micro- and macroaggressions, gentrification, the media’s need to cater to a white audience—and that’s just the satirical side. On the horror side, we’ve got witches, folklore, slavery and ultra-perms gone bad. The horror side works better, even if it doesn’t quite live up to its promise of a Vive-based verso battle featuring Vanessa Williams.

Williams plays Zora, the new head of Culture TV, an MTV-ish channel in mid-axis due to declining ratings. The “good-haired” Zora replaces Anna’s old boss, Edna (Judith Scott). This meant that Edna’s reign was very Afrocentric, evidenced by the addition of Grant Madison (James Van Der Beek), a white man with ideas to save the network. I was confused about Anna’s job. Was he even paid by Edna for all his years of work? Her father Amos (Blair Underwood in a shaggy gray beard) treats his daughter’s job as an internship and Anna can barely pay her rent. Anna’s big dreams are to become a VJ, although the station already has a quota of a black on-screen celebrity with natural hair, Siesta Sol (Yaani King Mondshen). Anyone else with less-than-dark-n-lovely hair faces unemployment. The worst moment of “Bad Hair” might be when Zora asks Anna “Who does your hair?”

There’s very little time that anyone discusses hair in this film, which is a problem because we never get a sense of what the women’s hair choices mean to them. Anna thinks straight hair will get her the coveted spot, but why weave? Seaman offers a flashback to a traumatic experience Anna had with a sedative that left her with a permanent scar. My aunt used to say they called it No Lie Relax because “it burns the hell out of your skull and that’s no lie.” Still, it’s easier and cheaper than knitting. “Bad Hair” spends more time dealing with mean-ass men like Anna’s thieving ex-boyfriend, Julius (Jay Pharaoh).

Career choices.

It takes about an hour for Viv to claim his first victim, though it gives Anna more than a little warning of his impending intentions. As much as I enjoyed Assassination Tactics, I still have a lot of questions. Movies like this need to move fast enough that we don’t focus on its inexplicable elements, and I don’t mean anything terrible. The material would have served better by either directly and uncomfortably confronting the subject matter it satirizes, as Spike Lee does in “Bamboozled,” or in favor of pure grindhouse tactics. By completely ignoring Playing with what the concept of good and bad hair means to its owners, “Bad Hair” fails to match the kind of dark experience that Jordan Peele pulled from “Get Out.” was The hirsute creature almost saves the film, but it misses by a hair.

Prey

“Prey” is worth the money to see on the biggest screen. The wide open spaces of Alberta look fantastic, there’s plenty of mayhem and action, and Sarah Schechner’s brilliant score deserves to be blasted through the biggest speakers available. So, why is Disney throwing an entry in the popular “Predator” series on Hulu in the middle of summer? The original “Predator” starring Arnold Schwarzenegger turns 35 this year. What better way to celebrate than with a prequel to any of its sequels? The marketing team could have had a field day developing this connection. So why is this movie, like Disney+’s “Turning Red” before it, going live streaming without a simultaneous theatrical presence?

Was it because director Dan Trachtenberg’s sci-fi actioner didn’t have a big star (aside from Predator, of course)? Was it because Patrick Ison’s screenplay was set in 1719, making it a period piece? Or was it due to the fact that the main character is a woman and her relatives are Native American, both bucking the trend of such films? Considering the recent cancellations of movies scheduled for upcoming release, I suppose I should be grateful that “Prey” can be watched anywhere, including on services I don’t subscribe to. That’s not to say that streaming services are bad, just that I’m always itching to recommend movies that require a contract to watch. Also, it deserves a theatrical release.

But I hesitate. “Prey” bills itself as the origin story of the first predatory alien to appear on Earth. It is equipped with a slightly retro version of the weapons of the late actor Kevin Peter Hall in the first film. The hunter’s modus operandi is the same, however: it’s a hunter and it’s looking for hunting trophies. This gives the creature a kind of sympathetic interest in Naru (Amber Midthunder), a young warrior who wants to hunt like the men of his tribe, including his brother, Tabi (Dakota Beaver). Naru is teased by the boys, who say that hunting is a man’s job, but we learn that she can hold her own in a fight. She looks as tough, and is three times more observant than the others. Naru is the first to notice that there is a new creature on their land. Perhaps it had something to do with the blazing line of fire he had seen in the sky earlier.

While searching for a tiger that has been walking about, Tabe can barely bear to tag along with Naru. They have an easy brother-sister relationship that Mud Thunder and Beaver develop almost immediately in their first scenes. Their bond adds to our worries when real danger appears. Naru sees and prints a leathery snake that does not belong to any known entity. “Something scared that tiger,” she tells Tabi, but he’s not in the mood for her claim that it’s a “monster from childhood stories.” Meanwhile, the hunter works his way up the animal chain, teaching a crafty wolf a lesson about selling wolf tickets by sticking out his spine. Naru is finally seen when he brutally braves the bear that has been chasing him and his loyal mutt.

The scene with the bear is so cleverly rendered that one wishes the “hunt” hadn’t given us a good look at the hunter beforehand. As it jolts the bear from its pursuit, raising it for the kill, the invisible hunter bleeds into the scene. Naru sees this and runs like hell. Thus begins a series of expertly crafted chase scenes, in which our antagonist uses both familiar and new methods to take out his victims. There’s also a callback to one of the original film’s best lines: “If it bleeds, we can kill it.” It bleeds a neon green blood which, at one point, is used by Naru as a war paint.

Adding another element of danger (as well as fresh meat for viewers hungry for hunter-based carnage) is a collection of exotic French fur trappers. When Naru stumbles upon a field of leather buffalo, she prays over them, thinking it is the work of a monster. He soon realizes that it is this man, the other demon hunter, who is responsible. Although they agree with Naru that something otherworldly exists, the trappers are even more sinister than the hunters. So we’re not sorry when they start sprinkling.

“Hunting” is a worthy successor to Ah Nald’s original, although there is no “Choppa” for anyone in 1719. She uses brains and brawn alike to handle all her enemies, dispatching them with fierce efficiency. Nature also proves to be a cruel adversary, but she is prepared for that too. The film creates a portrait of his Comanche nation and them like no other – they are the heroes of the story and the sense of camaraderie in their village. Although the film is mostly in English (apparently an entirely Comanche-language version was also shot in tandem).

Zora recommends a beauty salon run by Virgie (Laverne Cox). After Anna asks for an appointment, Virgie fits her in as her last client. “Are you gentle?” Virgie asked, leaning so hard on the word that it brought back memories of my mother’s comb running through my hair in my now-bald kitchen. This is followed by a heart-wrenching scene of Anna’s hair being stitched into the killer. It’s ridiculously over the top, with a memorably menacing Cox and a distressed Lorraine bolstering the scene’s effectiveness. All of the monster’s subsequent attacks are also leveled, which adds to the fun.

Seaman populates the film with so many additional characters that it feels more like a pilot for a TV series than a movie. This excess of characters worked for the director’s earlier effort, “Dear White People,” because it took place on a college campus and was a “day in the life” episode rather than a straightforward narrative. “Bad Hair” gives us underused characters like Anna’s co-worker Brooke-Lynn (Lena Wyeth) and Anna’s sister, Linda (Chant Adams). Linda is possibly interesting because she knows of an African folk tale that may have something to do with Anna’s weaving method. Scenes with Anna’s family feel out of place when they should be essential to the story. We should be more concerned with the myth-making elements of the folklore book in Linda’s case, rather than her relative’s ego shaming.

Temporarily suspend our disbelief.

Despite the expected groans from immature men who haven’t seen the movie yet but already think it’s “too woke,” “Predator” fans won’t be disappointed with “Prey.” It’s a scary and fun amusement park ride that also evokes surprisingly tender emotional responses. When Naru finally let out the battle cry he had been denied before, I couldn’t help but cheer. It’s too bad I couldn’t do it with an audience full of equally enthusiastic viewers.

Spree

It’s, like, so hard to make great content, you know? It’s a numbers game and right now I feel like a zero.” To Kurt Kunkel (Joe Carey), all of life is “content.” Using the internet handle @kurtsworld96, he talks about his life. makes videos, but has failed so far. Build yourself a following. In his world, your value as a human being is measured by how many people watch your live streams, or “like” your videos. He envies anyone who has achieved success as a social media “influencer.” or “personality.” He wants what they have. Told entirely through cell phone videos, dash cams, and CCTV footage, co-writer/director Yevgeny Kotlyarenko’s “Spray” is a strange and mostly unpleasant hybrid of social critique and horror comedy, revealing that this psycho kid. How does one decide to take off the gloves and become internet famous?

Kurt Kunkel is the Rupert Pipkin for the Internet age. He lives at home with his parents. He doesn’t have much going for him. He wants to be famous, even though he has no skills, talent, or even a charming personality. Then he gets an idea. He’ll be a rideshare driver, he’ll trick out cars with dashcams, and he’ll poison any passenger who bothers him. He will stream it all live. This will be a surefire way to “grow your audience”.

It’s all told in an absolutely riveting way, with non-stop blaring music, constant chatter from Kurt to direct camera, and a proliferation of screens, phone screens within phone screens within phone screens, rapid comments sections, text messages, DMs. . etc. Sometimes there is a split screen, sometimes the screen is divided into three. “Anxiety” feels like a day spent entirely on the Internet, jumping from YouTube to Twitter to Google to Tik Tok and back, never staying in one place for more than a few minutes…and I’m not sure. That this is a good thing.

Kurt’s murder spree is simple in that he only poisons the “bad” people: a racist white guy, a toxic bully who calls Kurt an “ansel,” a bunch of annoying party girls. . (It would have been more interesting if Kurt’s killing spree had been indiscriminate.) Kurt is angry that despite all the killing, he hasn’t gone “viral.” But then he picks up Jesse (Sashir Zamata), a stand-up comedian who built his brand mostly through his promotion on social media. When Kurt discovers how many followers she has, he becomes obsessed with her. He asks, “How did you grow your audience?” Jessie says, bluntly, “I’m funny.” He wants to tap her audience, he wants to piggyback on her “influence.” But how?

There are a few funny moments. David Arquette plays Kurt’s loser dad, doing a “DJ residency” at a strip club, and wants to talk to his son about “Disgust’s dope new track.” A little more of it would have gone a long way. Zamata, a “Saturday Night Live” alum, is gifted and sharp. It’s fun to watch. Even his silent reactions are amusing. There’s commentary buried somewhere in here, about how “influencers” have nothing to offer, and people like Jesse are different. He has talent. She will be doing her job with or without social media. But Kurt? All he has is “content”. To take it to its most ridiculous point, killing people is now his “content”.

The world of social media “influencers” provides rich territory for satire and criticism, aside from the main problem: the phenomenon is already a parody of itself. This situation presents a challenge for filmmakers who want to incorporate social media into their stories. “Unfriend” and “Friend Request” go the creepy route, effectively exploiting the general anxiety people have about social media. “Ingrid Goes West” had real bite, and her criticism of “influencers” (and those who imitate influencers) was merciless. Bert Marks’ “American Meme” was very depressing, and even though it was a documentary, it played like a horror movie. “Jawline” takes a more gentle approach, but the anxiety is still there: What does it mean to be a kid — with no real skills — who feels he has to “perform” for an audience? In the coming years, what will the age of social media look like? Does it seem like man just lost his mind for a few decades? It’s hard to know. “Trouble” doesn’t bring much to the table. You know when you spend too much time online, and your brain starts to feel fuzzy, or like a part of you is disconnected from your own overburdened nervous system? “Spray” feels like that.

Unsane

Steven Soderbergh’s “Unbreakable” opens from the perspective of a stalker. We hear in voiceover how the object of his affection made him see the world in a whole new way. And make no mistake. This woman is an “object” to this man, a person who has no agency or reality beyond what she can do for him. We later learn that the stalker is a man named David Strain (Joshua Leonard) and the woman is Sauer Valentini (Claire Foy), whom he meets while caring for David’s father in his final days. had been He became obsessed with her because of the comfort she provided to his father and David. In other words, she became something that made him feel good and so he felt a truly one-sided relationship, as they often do with stalkers. On the surface, “Unsane” is a potboiler, a routine stalker thriller. But it works because of how much is going on in this familiar structure, courtesy of Jonathan Bernstein and James Greer’s smart script, Soderbergh’s claustrophobic direction, and Claire Foy’s determined lead performance.

Sawyer is traumatized by her experience with David, and it has affected her professional and personal life in ways that lead her to seek therapy. She goes to a facility, tells her story, and fills out a few forms. Before she knows it, she is being asked to hand over her personal belongings and asked to disembark. He will have to stay for at least 24 hours for observation. Of course, she’s trying to get hold of her mother (Amy Irving), and even calls the police. When she mistakes an orderly for her hunter and kills him, her “sentence” is increased to seven days. She meets a menacing patient named Violet (Juno Temple) and an assistant named Nate (Jay Pharoah), who tells her that he is essentially part of an insurance scam, in which hospital patients like Enter only to collect money from your suppliers.

As if all of this wasn’t nightmarish enough, Sawyer is shocked to see David administering medicine to the patients. At first, she claims she has no idea who Sawyer is, and her admission of shock allows those around her to easily refute her claims that her stalker is at the hospital. I have entered where she is living. There’s an interesting subtext created by “Unsane” about listening to women when they tell you something wrong. The first doctor Sawyer goes to in a panic when she learns she has to stay doesn’t immediately hang up the phone to talk to him. A lawyer that Sawyer’s mother calls for help hangs up without waiting for questions or saying goodbye. And even the new role that Sawyer may or may not see in David is that of a controlling male: someone literally drugging the people in his care to make them behave this way. The way they want to do it. Without overplaying the gender dynamics in “Unsane,” Bernstein, Greer, and Soderbergh have something to say about controlling, not listening, needy men. (And there’s another commentary on the failure of our health care system that links this work to “Logan Lucky,” which was also, of course, the subject.)

And they say it with a bold new visual style. “Unsane” was shot on an iPhone and has an insane aspect ratio of 1.56:1. It’s somewhere between an old-fashioned full-frame ratio and traditional widescreen, creating a boxy look that’s perfect for a movie about someone who’s basically stuck. Once again, Soderbergh delivers such a brilliant economy of visual language, as he does in almost all of his work. It doesn’t feel like there’s a wasted shot here. (If anything, it feels like some scenes could have used a little more material.) For the most part, “Unhinged” is lean and mean, giving you what you want. Need to stick with it. And the visual style has an immediacy that adds intensity, especially in the early scenes when confusion reigns and most of all in a spectacular sequence that has already been called “The Blue Room Scene.” It feels like a style that leaves little room for the crutches of traditional acting or production, which puts more weight on Foy’s shoulders. She rises to the challenge with a complex, daring performance. She is very good here.

While Soderbergh does his best to elevate the material, the final act doesn’t quite live up to the weight of his best work as the script goes down a few roads that add too many plot holes and drag the work down overall. Reduces as It’s a bit disappointing to see “Insense” succumb to some conventional trappings in the final scenes, especially after having braved so much up to this point. Having said that, the first hour is so interesting, Foy is so good, and Soderbergh is so clearly still at the top of his game, that the relative failures of the climax can be forgiven.

After a brief retirement, Soderbergh is back roaring with two very different films in “Logan Lucky” and “Unseen.” Reportedly, he has already done another film

ear, and he directed the series “Mosaic” for smartphones and HBO. Not only is he back, he’s as active as he’s ever been. And the film world is better for it.

Lights Out

“Lights Out” began life as a three-minute short film by David F. Sandberg that was short on elements such as narrative complexity, character development and memorable dialogue (I don’t remember a single word being spoken). And long to come. . with larger shocks than would seem possible in such a short period of time. It received little attention and Sandberg was given the opportunity to expand the short into a full-length feature, putting it in the company of such esteemed genre figures as the original “When a Stranger Calls” and “The Babadook.” In the cases of these works, the filmmakers found ways to enhance the original shorts that were clever, dramatically interesting, and very scary. The problem with “Lights Out” is that while Sandberg’s “BOO!” Good to make. Moments — those quick shocks where something pops out of nowhere and scares the bejesus out of everyone — are deployed in the service of a story that has little to offer, and lose their impact after a while. Let’s start.

As was the case with “When a Stranger Calls,” “Lights Out” begins with a sequence designed to mimic the original short. Instead of an anonymous apartment, after hours in a factory, it begins as an employee (Lotta Luston, who starred in the short) sees a mysterious female figure in the dark who disappears whenever the lights are on. happens, and which is suddenly found. So close when they go out again. This time, however, she survives, while the factory owner (Billy Burke) meets a gruesome end. However, just before his death, he is on the phone with his young son, Martin (Gabriel Bateman), about how his mentally disturbed mother Sophie (Maria Bello) has apparently stopped taking her medication and She seems to be talking to an imaginary friend of hers. Diana. A few months pass and we learn that Sophie’s condition has worsened, and her conversation with Diana is so disturbing to Martin, not to mention the strange noises and scratches from all the attendants, that He can no longer sleep through the night and keeps passing out. in the middle of the school day.

When the school nurse can’t reach Sophie, she contacts her half-sister Rebecca (Teresa Palmer)—whose father mysteriously disappeared years ago and who has since suddenly moved out a few years ago. was separated from the sofa. When Martin mentions Diana, she recognizes the name from her traumatic childhood years and tries to get Martin to stay with her. This doesn’t fly with Sophie, and after reclaiming Martin, Rebecca tries to get to the bottom of who or what Diana might be and how she relates to her family. Without going into too much detail, he is now a creature that can only attack in the dark and cannot be around any kind of light. After two of Diana’s attacks, Rebecca, with the help of friendly boyfriend Brett (Alexander Depressia) and Martin, decides to break into Sofia’s house, lighting the whole place up in the process, so that she can take her. start going . Re-medicate and seek treatment for his instability. Alas, Diana thrives when Sofia becomes extremely distraught and starts turning off the lights to get rid of each other once and for all.

Although Sandberg is the director, the big name behind the scenes here is co-producer James Wan. His genre bonafides include the “Conjuring” and “Insidious” franchises, films that largely eschewed the gory excesses of his hit “Saw” in favor of low-fi thrillers that rely more on atmosphere. For example, small-scale effects (such as door hinges) and objects suddenly appearing out of nowhere. When done right, as was the case with the original “Conjuring” and “Insidious,” the results can be thrillingly effective, like the best haunted house ride ever created. Get it wrong, however, and the results can be like sequels to “The Conjuring” and “Insidious” — increasingly tiresome efforts that constantly try to squeeze in extra screams that are too familiar for its own good. .

It doesn’t take a genius to figure out which of these modes “lights out” after just a few minutes. For example, what made “The Conjuring” so good is that even though it was a horror show at heart, it still took the time to create characters we cared about, a In developing a plot that doesn’t stress at all. Beliefs were bound and feared so that we did not know what to expect next. In comparison, the film has two strong actresses in Teresa Palmer and Maria Bello but then fails to find a way to utilize their talents. The story is ambiguous in such a way that despite a lot of exposition, it never fully conveys what Diana is supposed to be or the extent of her powers. As far as scares go, there are few effective shocks. But by the time it finally closes (though it only closes at 80 minutes, “Lights Out” still feels

Even the most anxious moviegoers will find themselves surprisingly calm and relaxed.

“Lights Out” is made with a certain amount of style — enough to make you see what Sandberg might be able to do with a better screenplay — and it has one great moment that Pays tribute to the world’s most famous moment. The classic thriller “Wait Until Dark.” For the most part, though, the film is just a tired run through of the usual elements, and that might be enough for those looking for some cheap thrills on Saturday night cable at home, but it’s hardly Be aware of their efforts. Going out to see. And yet, with the current dearth of horror movies — with the exception of “The Shallows,” an example of a genre entry that’s managed to take a familiar premise and turn it into something fresh and interesting — Ho Can paint enough—increasing demand for a film of its kind to make it a success and start another franchise. If so, here’s hoping the filmmakers do something smart next time.

Shadow in the Cloud

Roseanne Liang’s “Shadow in the Cloud” is the kind of movie that makes a lot of its weird choices just to see if it all works. But whether you find the film ambitious, or just some stunt screenwriting, it’s interesting to see an intrepid filmmaker try to keep midnight-ready movies unpredictable, even if that means WWII dogfights. , a sincere but silly mash-up of Gremlin Chaos, and feminism in the process.

Before the parade of production company logos is complete, “Shadow in the Cloud” opens with a great mystery — why am I watching a WWII-era cartoon PSA about gremlins? Consider Chekhov’s Gremlin infomercial, with the next shots of the film showing a revolver being packed, and a suitcase with a sound hole. The year is 1943, and a woman named Maude Garrett is walking on a foggy tarmac after an Allied warship named “The Fool’s Errand” before we see her face and hear her voice. It’s a stoic Chloë Grace Moretz, with a British accent, and a top-secret mission assignment. The men act like dogs as soon as they realize they have a “dam” on board – most of them scramble to object to her on the radio – and get her to sit in the lower turret. Nominated, along with the boys above. Mahuia Bridgman-Cooper’s synth score sets the pulse right from the start, signaling that you should be prepared for a film with modern tastes, not an accurate period piece.

From here, “Shadow in the Cloud” builds slowly, at first like a theater piece about a harassed woman, physically removed from the prospect of standing up to them. Along with his rude comments, those on board question his credibility and mission, though a boy named Quaid (Taylor John Smith) stands up for him against the others. This first act mostly features Moritz inside the bridge, and is credited to his performance but also to the film’s depiction of a claustrophobic space that feels almost impossible to pass. Sometimes, you have to remind yourself that you haven’t seen as many men as you think. Although Liang cheats in some instances to show what’s going on above (with the stage, with dreamlike imagery of red and green lights), it’s a strong case of scenario and accurate dialogue. Lets the imagination fill in the blanks, and make us. Adequately hated.

Titane

Love is a dog from hell” reads the tattoo between Alexia’s breasts, just one of many dotting her frail frame. This tattoo is a red flag to anyone and everyone who loves Alexia. Wants to get close, not just close to her breasts, but close. Usually to her. Most people ignore the red flag. Maybe they just think she’s a Charles Bukowski fan. Whatever. Be that as it may, they don’t “get” Alexia.” French filmmaker Julia Ducournau’s gripping body horror “Titan” centers on the titanium plate holding Alexia’s skull together after a childhood car accident.

As with Ducournau’s feature debut “Ra,” “Titane” explores the frailties and desires of the body, its horrific practices, and how the collective “we” try to cope with it all, either by surrounding ourselves or , on the contrary, by sublimating. Need in other things. Neither action is pleasant and/or socially acceptable. You cannot naturally control the uncontrollable. “Titan,” winner of this year’s Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival, is an extremely violent and brutal and funny film, but the space it provides for not just tenderness but contemplation makes it an “extreme” concern. Makes a compelling film. Okay fine

Whatever is “wrong” with Alexia, and quite wrong, pre-dates the accident that cracked her skull. She is first seen, a dead-eyed “bad seed” type child (played by Adele Gigg), beaming at her father as she makes engine noises in concert with a moving car. It’s hard to avoid the idea that she wants the car to crash, or at least wants it to. Leaving the hospital, a cluster of scars swirling around her half-shaved head, she throws her arms around the car, kissing the window. An exciting reunion. Years later: Alexia (now played by Agathe Rousselle), head still half shaved, makes a living at car shows. She is a lonely and forbidding figure, even more so when she suddenly kills an aggressive fanboy who follows her to her car. Later that night, she crawls into a flame-painted gas-guzzling Cadillac for another passionate reunion, only this time it’s sexual. Car sex results in pregnancy and a titanium-plated Alexia stares in horror as her stomach bulges out, her breasts ooze motor oil, and her vagina oozes black oil in the shower. His body is now on a journey that does not involve him.

Meanwhile, the bodies piled up. Alexia is a ruthless killer. These murders are very gruesome. After leaving the witness in the murder, she is forced to go on the run. When she sees a computer-generated image of what a famous missing child named Adrian would look like today, Alexia has a brilliant idea. Without hesitation, she breaks her own nose, binds her breasts and pregnant belly, and goes to a police station, posing as the long-lost Adrienne. It’s such a perverse and ridiculous plot twist, and it signals the second half of the film, which is very different from the first. Adrian’s father Vincent (an excellent Vincent Linden) is a muscular fire chief who breaks down in tears at the sight of his son. Alone at night, he shoots himself up with steroids, shoves the needle into his bruised ass, his body now a veined tortured face of failed invulnerability.

But appearances are not what they seem. Vincent isn’t her level, just like Alexia isn’t hers (or Adrien isn’t hers). The firehouse is a manly world of half-dressed men, and yet the decor is gender-coded, the interior lighting soft neon pink, the bathroom tiles bright pink. As the first half of “Titan” is full throttle, it’s the second half where things really take off, where Ducournau digs deeper into her subject, wading into very strange and complex waters. Alexia isn’t so much a character as she is a wild-eyed figure from Fight or Flight (albeit pregnant with a baby born from a Cadillac). But Vincent… Vincent is a real character, and Lyndon brings deep insight to the table, revealing the confusion and fear of the little boy that grows beneath those muscles. Metaphors are manifold, and Ducournau cleverly keeps things fluid, allowing things to work visually and/or in contrast to how they work clearly in language. There is a scene where Vincent, eyes dumb with grief, buries his head in Alexia’s lap. Both figures are bathed in pink light. This Pietà image carries a lot of weight metaphorically.

The language of caring for each other comes up again and again. What does “care” even mean in the world of “Titan”? Everything seems so dangerous and temporary! The importance of tenderness—and the softness of pain for those unaccustomed to it—is in stark contrast to the inflexibility of the human body, the body’s irritability and fragility, magical titanium plate or not. These various conflicting views don G together all the time, and “Titan” sees between its horror first half and family melodrama second half (making it top-heavy or bottom-heavy, depending on how you look at it). Deep thematic revelations may come too late in the game for those turned off or turned on by the brutality of the first half, but Ducournau, inventive, daring, fearless in his approach and sensibility, manages to hold his nerve. does not lose Neither is “Titane.”

Run

It’s the follow-up to the guys who made 2018’s “Searching,” starring John Cho, in which John Cho searches for his missing daughter, using (almost) entirely a laptop and cell phone. happened within the confines of the screens. . . It was a gimmick, but brilliantly executed, and it allowed Cho to deliver a tour-de-force performance in a situation where there’s no hiding place.

With only their second feature, director Anish Chaganti and his co-writer, Sev Ohanian, expand the scenario but maintain the same focus on narrative. And even when things get a little off-kilter toward the end in a way that detracts from the quiet, slow burn that preceded it, the performances in what’s essentially a two-hander are always gripping. We’ve seen Sarah Paulson do this kind of craziness under the surface for years, but it’s always cool to see. Her technique is very specific, and she keeps you ahead with the slightest facial expression or unexpected line delivery. But the great discovery of “Run” is Kiera Allen, making her feature film debut. As if performing opposite one of the greats working today wasn’t hard enough, “Run” asks a ton of Allen in a physically and emotionally demanding role, and she’s up for every challenge. She is a real find and a joy to watch.

“Run” begins, though, in a quietly disturbing way. With echoes of the Ryan Murphy series “Ratched,” we see Paulson’s Diane Sherman in a hospital where everything is bathed in a sickly green light. She has just given birth to a premature baby, and the title card lists various ailments, including arrhythmia, asthma, and diabetes. Seventeen years later, we see Diane living a highly regulated but apparently happy life with her daughter, Chloe (Allen), who goes about her daily routine in her wheelchair. (Casting an actress with a disability for the part also makes Ellen a perfect choice.) In addition to medication and physical therapy, there are home school hours, which Diane manages. Mom also cooks healthy meals with vegetables grown in her garden. Everything is carefully controlled. Chloe is clearly an intelligent young woman, as evidenced by the many complex engineering projects she works on in her bedroom, and seems to have a bright future ahead of her.

Yes, that’s it. Chloe dreams of leaving home and her isolated town — and her mother — to study at the University of Washington, four hours away. It’s not like they have a dysfunctional relationship. It’s just that it’s been just the two of them in this remote house for so long, and since Chloe hasn’t been allowed access to an iPhone or the Internet all these years – which is a little suspicious – she A yearning to explore beyond understanding. . The way Diane defensively insists during the Dunya support group meeting that she’s perfectly fine with the possibility suggests that maybe she’s… not.

What makes “Run”‘s clockwork tick comes from the small details and edits, the work of Nick Johnson and Will Merrick. Following their normal schedule and observing slight changes along the way, we get the sense that there is a disturbing change underfoot. Part of the fun of “Run” is that, as in “Search,” we’re solving the mystery of what’s actually going on alongside the main character. A great example of this approach occurs in Pharmacy when Diane and Chloe go into town to see a movie (and the marquee title is good for a laugh). We’re putting the pieces together as Chloe is, and we can feel her nervousness as the tension continues to build. Later, in one of the film’s more physically demanding scenes, Chloe must get MacGyver out of a difficult situation, but the reality is that Chaganty and Ohanian underpin her intelligence and resourcefulness. , it’s a blast to watch, and not at all. . Many of the funny Allen’s scenes require him to act alone and pull us along for nothing, which would be difficult even for a seasoned actor, but there’s a wisdom and confident quietness about him that’s compelling. And there is a foundation.

And that’s crucial, because “Run” gets a little wilder as it barrels toward its end — less Hitchcock, more “Trouble.” But within this big reveal are some unexpected twists and turns about what’s really going on here. And during these awkward times when we’re all stuck at home by ourselves, a “run” might just be the escape we’ve always needed.

Little Monsters

“Little Monsters,” in which a class of Australian kindergarteners find themselves surrounded by the undead on a farm field trip, handles zombie comedy with kid gloves. The key to their survival is their teacher, Miss Caroline (Lupita Nyong’o), who manages to convince the youngsters that it’s all part of a game, and initially has little help from the naïve Dave (Alexander England). meets, and a tormented child played by TV host Josh Gad. It’s all over-the-top and just not funny enough, even if it’s a blood-soaked tribute to those who will see the story as just another day of low-wage work.

Nyong’o turns out to be the highlight of the film, and at least her character proves that she’s game for the funny, and (later in the film) can master a dry witty monologue. . Along with Jordan Peele’s “Hum” proving the Oscar-winning actor’s multiple talents, you should hear Taylor Swift sing “Shake It Off” here, while (actually) playing the ukulele. Even when she’s not sporting a dangerously soft mezzo-soprano voice, Nyong’o is a life force for “Little Monsters,” cutting through the boisterous buffoonery of her male co-leads.

But instead of focusing on Miss Caroline, “Little Monsters” is, surprisingly, about a guy with a lot to do: grungy, 30-something Dave. He’s introduced to the film by fighting with his girlfriend in the opening credits—watching them fight in different places, unable to hear what makes them both angry, the camera vignettes around them. floats like One would expect a zombie to pop up, but no dice. Instead, the story takes about 20 minutes to establish him as a recently broke, heavy metal (channeling some big 2000s Jack Black energy) who is looking for his nephew, Felix (Diesel Law). Is loud and oblivious like his classmates. Toraka). Tired puppy dog that he is, Dave’s fixation on wooing Miss Caroline turns when he meets Felix one day dropping off school.

In an attempt to impress her, Dave offers to help Chaperone take a class trip to the farm, which happens to be near a US Army base. But before the zombie outbreak happens next door, things already turn disastrous for Dave when he learns that fighting these kids isn’t as easy as he thought, and that he has Miss Caroline’s. There is no accompanying shot. He is especially frustrated against Teddy McGiggle (Gade), a child entertainer from America on a world tour who knows how to attract a young crowd, and sweet-talking women like Miss Caroline. . His chances shot down, Dave panics, until the monsters eventually force the class and three adults to sneak into a souvenir shop.

Writer/director Abe Forsyth crafts a relatively simple zombie takeover, which is a big nod to the film’s limited creativity. Yes, there are decomposing human beings walking around and sometimes popping out of “The Walking Dead.” But there’s little inspiration behind the zombies themselves, who don’t raise any nerve-wracking stakes (even with kids in the mix), or behead in thrilling ways. Nyong’o even has a sequence where she dives into a zombie battle, but the film pulls away from that, only to show her clothes and hair covered in blood and guts afterwards. It’s yet another example of “little monsters” overshadowing even the tiniest of gratuitous pleasures—how can you get Oscar winner Lupita Nyong’o going ballistic on the undead, and then not us? Can show?

The zombie apocalypse of “Little Monsters” takes place mostly during the day, a key detail in how the film aspires to balance lightheartedness with dark comedy. But Forsythe’s script lacks the cleverness to make such a tone pop, instead filling the moments with simple, corny jokes, such as God’s frequent falls to the ground, or Dave’s accidental heroics. Watch as it progresses. “Little Monsters” also has a stereotypical joke about Asian tourists taking photos, and it would be more offensive if it didn’t seem to be par for the film’s shallow course. I laughed a lot when a Mad God aggressively berates the youth—a moment in which adults are oppressed through the innocence of youth—but perhaps knowing how ridiculous the beat is, and After not being able to think of anything else, “Little Monsters” then repeats. . Again and again, the shock loses its luster.

“Little Monsters” isn’t for kids, and yet it wants to be as cute as their singalong, even just from its premise. More than any typical comedy, your mileage will undoubtedly vary with “Little Monsters,” especially if you find children (with their matching bags of frogs and little observations) lovable, or humans and children. Able to connect instantly. But as someone who has consistently struggled to have absurd fun with “Little Monsters” — his self-fun is more than contagious.

Censor

Do you remember horror videos from the 1980s? You don’t really need one to appreciate “Censor,” a British psychodrama about a film censor’s personal relationship with the violent films she reviews and prices for a living. Realistically, that’s all you need to know about the Video Recordings Act of 1984 and the moral panic it caused: some successfully prosecuted (30+), as well as some frowned upon. Editorials, legislation, and protests, and a bit of over-the-counter consumerism.

Today, video nasties — a diverse collection of disturbing films including “Blood Feast” and “Faces of Death” — are a convenient symbol of certain period pressures. They are still a good Rorschach test for personal anxiety. The makers of “Censor” go with the latter interpretation, and do a good enough job of contextualizing a woman’s struggle to understand why she’s drawn to scary horror movies.

The answer is simple enough to understate, but still fundamentally true: mousy Enid (Niamh Algar) has unresolved family trauma, and through her work as a film censor at the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC). It is being processed. Enid began in particular because of a controversial news story: a Bragg House resident supposedly killed and ate his wife’s face after watching “Deranged,” a 1974 horror film about a serial killer necrophiliac. Saw both and was impressed. Somehow, the British press has discovered that Enid and a fellow censor have passed “Deranged” despite BBFC certification and the need for “extensive” cuts before UK release. Tensions flare, but not serious enough to threaten Enid’s job.

Thankfully, “censor” isn’t some pointless reaction to “Deranged” or similar films that were either successfully prosecuted or flagged for possible confiscation. Rather, “Censor” is about Enid’s growing infatuation with Frederick North, a fictional director whose title work (“Don’t Go to Church,” “Asunder,” etc.) indirectly reminds her of a private trauma: Missing is Enid’s sister Nina (Amelie Child Villiers), whose death certificate was recently signed by Enid’s parents. Closure is what they want—Nina’s case is cold enough, and her body was never found—but it’s the last thing Enid is comfortable with, given her line of work. So End becomes obsessed with finding Alice Lee (Sofia LaPorta), who has recently disappeared from North’s films. Her investigation clearly does not lead to the catharsis she hopes for. But that’s part of the movie’s charm: Nobody really gets anywhere by talking about violent movies.

Some of the most satisfying parts of “Censor” are the final conversations that Enid and her colleagues have about the necessity of their jobs. Some see themselves as righteous cogs in an inefficient, government-sponsored machine. “How can we do our job properly when we are constantly mired in government bureaucracy?” asks Gerald (Richard Glover), one of the four letters of “bureaucracy” makes a perfect meal.

Other sensors are genuinely concerned and/or wary of the material they are supposed to be examining. “What’s with these directors?” asks Ann (Claire Perkins).

“Male inadequacy; the catharsis of revenge” Enid replied with a cheeky smile. He might have answered it before, if only in his mind.

Ann persists: “Doesn’t it bother you?”

But Enid is not so easily understood, not anyway. “Just focusing on getting it right,” she insists. “Don’t even think about anything else.”

“Censor” inevitably becomes a trite, but moody exploration of Enid’s repressed feelings, mostly about Nina, but also about her work. Enid looks for clues everywhere, first at a local video store run by a clueless clerk—and then with North’s proudly obnoxious producer Doug Smart (Michael Smiley). The answers he and his creators come up with aren’t exactly important, but they don’t need to be. The constant threat of seeing something forbidden is still palpable and thrilling.

So while Enid’s investigation never goes unremarkable, “Censor” still develops an increasingly frustrating, anxiety-inducing effect. Parts of the film were shot on film (35mm and 8mm) as well as video, and this is part of the film’s charm. But really, as a symbol and as a character, the best thing about Enid is that she never gets anywhere.

The Aeneid is a cliché of strict conservatism, as we can tell from its scholmarum appearance. She wears her hair in a bun. His aviator-shaped glasses are attached to a gold chain around his neck. His skin is half and half alabaster. She lives to take the viewer deeper into her increasingly desperate search for satisfaction. “Censor”, in that sense, is a success, if only because it envelops you, and leaves you wanting more of where it came from. There are many great books about fearing video nasties—two quick ones